At the beginning of the 20th century, Chamonix was just a simple mountain village whose growing fame was linked to its unique geographical location and the fact that this locality was the starting point of “the road to Mont Blanc.” By this term, it meant the long route that mountaineers, with or without a guide, had to follow to reach the summit of Europe.

At this time, the idea was born to shorten this road from Chamonix by building an “aerial cable car” joining the valley to the summit of the Aiguille du Midi.

A group was formed in Switzerland (Marc Eugster) and France (Léon Estivant and Emile Dollot). These precursors had no idea of the difficulties awaiting them with the still embryonic technology that could be used to carry out such a project. It should be noted, moreover, that skiing was still only a sporting entertainment little practiced. Still, it would develop, and Chamonix, as a result, would become a flourishing winter and summer resort.

On June 2, 1910, work could begin following the signing of agreements between the Municipality of Chamonix, the land owner, and the Aiguille du Midi-Mont Blanc Aerial Funicular Company. The starting point of this first cable car line was fixed at the village of Pélerins, two kilometers downstream from Chamonix, where the station was built. It can still be seen at number 1207 of the current road.

A 65-year operating concession had been awarded to the Company. Still, this concession often had to be renegotiated because of the difficulties encountered on the ground, the impossibility of reaching the summit of the Aiguille using techniques of the time, and changes in the companies successively in charge of work and operation.

When the First World War broke out, the project was interrupted. The Company suffered severe setbacks as Marc Eugster, its major shareholder, was bankrupted mainly due to his bad business dealings. A new company replaced the first one in 1922 under the name of Société Française des Chemins de Fer de Montagne. Aiguille du Midi Mont Blanc network. Work was ready to resume with the support of Joseph Vallot, a famous astronomer and geographer. Twelve years had just passed, and no connection was yet operational.

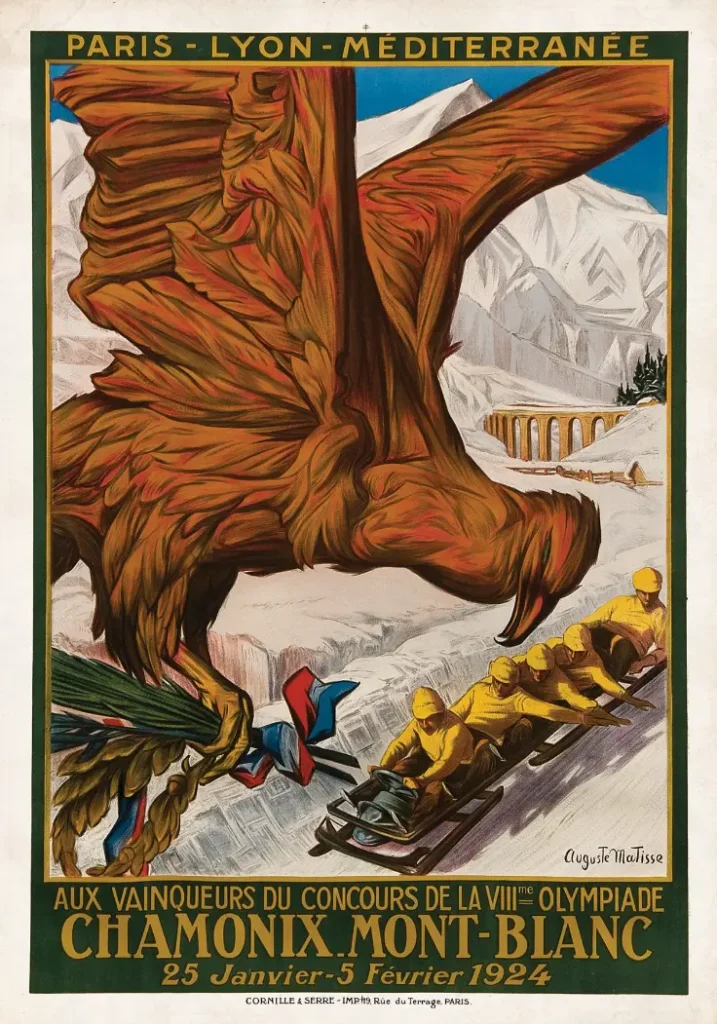

The first Winter Olympics in 1924 would accelerate the construction of the project. Chamonix’s candidacy was officially approved in June 1923 by the IOC, and development work began. The Pélerins forest, crossed by the first section, was chosen to develop the bobsleigh competition track, a sport more popular than alpine skiing then.

The Para intermediate station (1685m) was built and opened on time (it is still in the forest). The first connection from the Pélerins took place during the Olympic Games. However, the wire drawing works of the time could not manufacture a cable of 1800m range in one piece: this is why an ingenious system made of a double tower connected by a 15-meter rail made it possible to use shorter cables. This type of tower was carried away by an avalanche on May 17, 1983. This tower was called “the stop of the bobsledders” because the competition track started at this place.

In August 1927, the second section linking La Para to the Gare des Glaciers (2414m altitude) was opened to tourists. Although still at the foot of the Aiguille du Midi, the cable car received the world’s title of the highest ski lift. This success was snatched from it shortly after by the Chamonix-Planpraz-Brévent cable car, located on the other bank of the river Arve in the Aiguilles Rouges massif.

In May 1933, severe financial difficulties led to the bankruptcy of the Society. Equipment and installations were put up for sale at a public auction. The Aiguille du Midi remained untouched by any human construction.

It was in 1936 that a former artillery commander, Henri Durteste, acquired the company by joining forces with Léon Estivant, an engineer from the Ponts et Chaussées named Baticle, the contractor Louis Billard and the former fighter pilot Henri de Peufeilhoux.

The new company took the name Compagnie française des Funiculaires de Montagne. Things seemed to improve due to a more efficient commercial policy with, for example, the creation of a ski run from la Para to the Pèlerins.

It should be noted that Henri de Peufeilhoux, who later took over operations management, came to a tragic end during the war. Following a sudden power failure, the service bucket of the third section stopped abruptly, and he found himself ejected from the platform into the void. He found death in this vertiginous fall.

In 1937 the Company’s operating results were finally positive: coach shuttles took tourists to the departure station directly from Chamonix. A train station linking Chamonix to Fayet had been opened close to the departure of the cable car. This station bore the name of “Aiguille du Midi station” (it was later renamed “Les Pélerins”), and a direct route led travelers from this station to that of the cable car. However, the construction site still had not reached the summit of the Aiguille. It was then decided to change the final destination and only to reach the Col du Midi (3600m), close to the summit.

Twenty-seven years had passed since the laying of the first stone and the signing of the first agreement, but the Col du Midi, a good tourist destination, would provide access to the Vallée Blanche ski area and shorten the ascent route to Mont-Blanc, followed by mountaineers. Then the war came again in 1939.

In June 1940, a temporary link to the Col du Midi was established from the Glacier station. There was not yet a dumpster, but a wooden tray called a “service dumpster” replaced it, giving the trip, in the middle of the mountains, an undeniable acrobatic character. The war and the occupation interrupted the work, and there was only limited activity until the liberation.

In 1945, the cable car was not a priority in terms of construction due to the general state of France after the war. In 1948 construction activities on the route of the third section ceased definitively.

In 1949, another project was born: take the route from Chamonix and arrive directly at the top of the Aiguille du Midi, abandoning the Col du Midi. A new cable car was going, in the future, to replace the first one, which took the name of the cable car of the Glaciers.

In 1950, the text of the new concession agreement for the future cable car was drawn up with the Compagnie du Téléphérique de la Vallée Blanche, which had replaced the Compagnie Française des Funiculaires de Montagne.

The year 1950 sounded both the death knell for the old route, facilities whose construction had lasted about forty years without being finalized, and the advent of its successor. Its route starting from Chamonix itself, an intermediate station at the Plan de l’Aiguille (2310m), and arrival on the Aiguille du Midi were undeniable assets. The design of such a site was based on new technology and significant financial resources, which made it possible to carry out the work in a few years.

Therefore, this cable car, managed by the current Compagnie du Mont Blanc, is what you are now using. At its Plan de l’Aiguille intermediate station, looking towards the Glacier des Bossons, you can see some ruins of the old Glaciers cable car still clinging to a mountain it never reached.

Related reading: